“These layers were formed from thousands of years of A.I. slop.”

Cartoon by Adam Douglas Thompson

Anyone who is familiar with anime, or Japanese animation, knows that it often focuses on themes and stories of environmentalism. Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind (1984) and Princess Mononoke (1997), both directed by Hayao Mizayaki, Isao Takahata’s Pom Poko (1994), Makoto Shinkai’s Weathering with You (2019)—these are but some examples that, in different but interconnected ways, explore the relationship between humans and the natural world.

To this list we may add Wolf Children (click to view on Crunchyroll), a 2012 anime feature directed by Mamoru Hosoda, even though the film does not seem to have strong environmentalist themes at first sight. Telling the story of a young woman, Hana, who falls in love with a werewolf and, following his sudden death, must raise two half-wolf, half-human children she has with him, the film is ostensibly about the trials and tribulations of raising children. With its focus on the family, the film’s connection with ecocinema appears tenuous at best. In fact, this had been my view of the film until I read David John Boyd’s perceptive essay “‘Wolves or People?’: Lupine Loss and the Liquidation of the Nuclear Family in Mamoru Hosoda’s Wolf Children (2012)” in Journal of Anime and Manga Studies. For disclosure, my observations below draw heavily on Boyd’s analysis in the essay.

There are two important contexts to consider in connection with the ecocritical perspective of Wolf Children. The first is the 1905 extinction of the Japanese Honshu wolf, which, as a figure celebrated and worshipped by Japan’s rural ancestors, is tied metaphorically to Japan’s premodern identity. In this sense, the vanishing of the Honshu wolf, to which the ancestry of the werewolf father in the film can be traced, can be viewed as alluding to the larger extinction anxieties that have loomed in rural Japanese communities threatened by a similar reality of socioeconomic, cultural, and environmental erasure: deforestation, urbanization, corporate land development, and so forth.

For the Honshu wolf and the premodern Japan it symbolizes, the threats to their existence were brought about by the Meiji Restoration, during which time Japan rapidly industrialized and adopted Western ideas and production methods. This process would continue and intensify in the postwar period, and decades of unbridled development and a keen adherence to nuclear power, coupled with a weak social welfare system, corrupt corporate-conservative policies, and the alienation of an ultra-technologized world, ushered in a new level of social, economic and ecological precarity (e.g., the extended period of economic downturn following the bursting of the bubble economy in the early 1990s; the threats of nuclear disaster), one that pertained not just to lupine loss and the disappearance of premodern Japan but to mass precariousness across the country.

This brings us to the second major context for Wolf Children, namely the Tohoku earthquake, tsunami, and Fukushima nuclear meltdown on March 11, 2011. From the latent radioactive effects of mass contaminated farmland, livestock, and fresh water sources to the destruction of homes and lives and the mass displacement of people, the social, economic, and environmental crises following 3/11 dwarfed the scale of the renewal efforts that had helped Japan rebound from previous calamities (the Kanto earthquake of 1923; the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki at the end of WWII) and further exposed and intensified the cracks in the social fabric of Japanese society. All this prompted an intense self-reflection; most importantly for my purpose here, there were widespread critiques of the nuclear family as an institution. Epitomizing a postwar social contract in which mothers and fathers found themselves locked into private and public realms of domestic-corporate labor while the child functioned as the vessel fulfilling the dreams of a prosperous, reproductive future, the nuclear family had come to be seen as a symbol of Japan’s developmental state. And insofar as the 3/11 catastrophe laid bare the problems of Japan’s industrialism and, by extension, nuclearism, it also made people take a more deeper and more critical look at the nuclear family and its complicity to the mass precarity of contemporary Japan.

It is in this conflation of ecological and familial semiotics where the ecocritical perspectives of Wolf Children can be observed. Broadly speaking, the film can be divided into three parts. In the first part, we witness the failure of the nuclear family (with its ideal of bourgeois prosperity) in contemporary Japan: the wolf-father is lost to the precarity of breadwinning, which leaves Hana desperately trying to learn how to be a young mother without any help in the alienated environment of Tokyo. Her predicament is expressed succinctly in the scene where she, with her ailing daughter in hands, is stuck wavering in the middle of a street framed by a pediatrician practice on one side and by an animal clinic on the other. This captures the central binary of wolf/human—and nature/culture—that recurs throughout the film.

In the second part, we see Hana move to the countryside and learn to grow her own food and take care of her children with the help of a closely knit rural community. It is in this pastoral and communal space, with its remnants of the preindustrial stem family, that Hana is able to find an alternative to the city and to the Japanese nuclear family overdetermined by the postwar dreams of modernity, prosperity, and advancement. Instead of deciding the future path her children should take, she allows them to grow as both human and wolf, and their new-found freedom is movingly reflected in the intense animalistic energies that permeate the scene of the pack running through the idyllic snowy landscape of the mountains.

In the third and last part, we see the different responses of the children—Yuki and Ame—to their werewolf identity as they grow and find their own paths in life. Yuki chooses to become more human so that she can better assimilate at school and to the human world at large. Ame, on the other hand, seeks to leave human society altogether to become a guardian of the mountains, protecting the environment that is under assault by the modern Japanese state and filling the absence of Yuki, his father, and his extinct species. With the different choices of the siblings, Hosoda offers two interventions into the institution of Japanese nuclear family: first, Yuki’s path of hybridizing the family, offering possibilities for both integration and change; and second, Ame’s rejection of the family altogether for the endangered ecosystem.

In either case, Wolf Children interrogates a modern capitalist Japan, destabilizes one of its key ideological and institutional extensions, namely the nuclear family, and considers alternative futures through allegorical representations of nonhuman becomings (Yuki) and familial unbecomings (Ame). In doing so, Hosoda offers hints as to how the Japanese nuclear family can mutate and adapt to the current strains of socioeconomic and ecological pressures.

Man Fung Yip is an Associate Professor and Department Chair of Film and Media Studies at the University of Oklahoma.

There may not be many wild places left on Earth, but Antarctica certainly is one. Winters are extremely hostile to life – certainly to human life – with extremely cold temperatures and months without sunlight. Even summers are cold, and the weather is dangerously moody. The sheer size of this ice-covered continent is breathtaking. It is much larger than Europe 14,200,000 km2) and essentially unpopulated except for a few researchers in a couple of stations and some tourists who reach the Antarctic peninsula on cruise ships during the few weeks this is possible to cross the treacherous Drake passage between Patagonia and Antarctica each summer.

Continue reading

This post was co-authored by

Mariëlle Hoefnagels, University of Oklahoma, Dep’t of Microbiology and Plant Biology

and Amanda Boehm-Garcia, University of Oklahoma, Fred Jones Jr. Museum of Art

Art can highlight environmental issues and be a vehicle for change. While the role of art is as varied as the artists who create it, there are those whose practices intentionally challenge our perspectives, raise awareness, and pose difficult questions to give shape to the world around us. This approach is akin to the impetus that drives the sciences. Many artists, such as American photographer Patrick Nagatani (1945-2017), have melded the methodologies of visual language with detailed scientific study to raise public consciousness about environmental distress.

Continue reading

On a cold morning after a winter storm, I start my day by putting a green bin at the top of my snowy driveway. Walking the dogs a few minutes later, I observe the pattern of brightly-colored containers in front of houses as if they were signs, green symbols of allegiance to compost, an ancient and Continue reading

Introduction

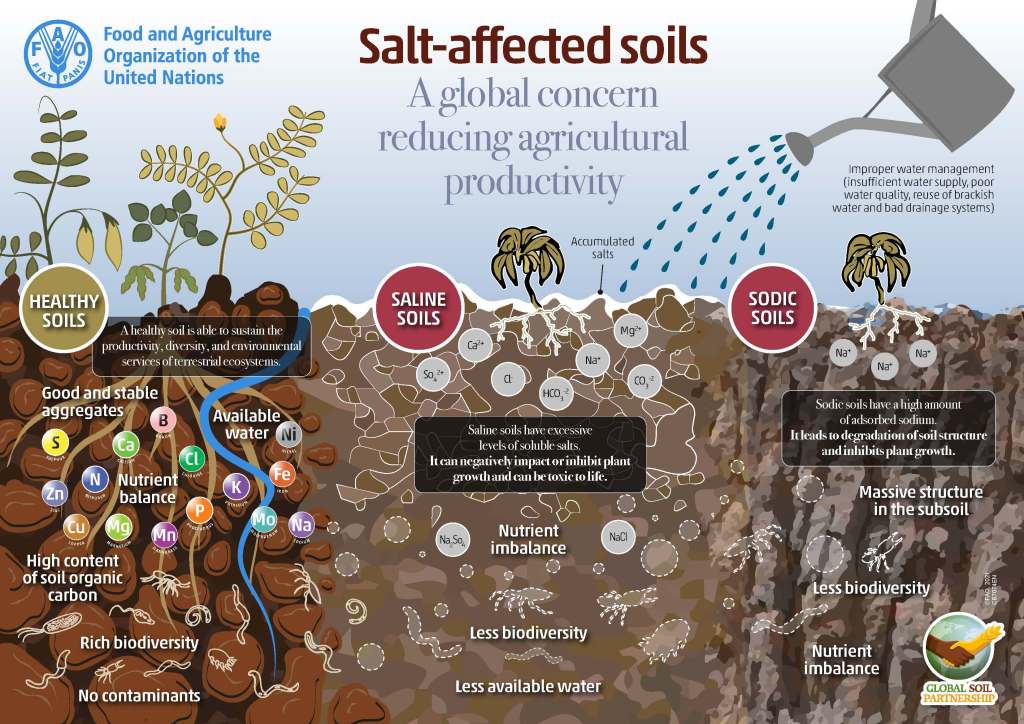

Every December 5 the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) of the United Nations recognizes World Soil Day. Through this celebration, the FAO acknowledges the importance of soil as a resource – in other words critical infrastructure – and sets a theme of soil science education for the subsequent year. This year the said theme is “Halt Soil Salinization, Boost Soil Productivity.”

Continue reading

Soil profile (northern France). Notice the distinct horizons— darkest at top, where it’s most organic rich and—below that— various shades of brown that reflect leaching and accumulation of minerals over the millennia of formation of this soil. All photos by author.

Infrastructure— “the set of fundamental facilities and systems that support the sustainable functionality of households and firms. Serving a country, city, or other area, including the services and facilities necessary for its economy to function.” [Wikipedia] Continue reading

Academics are a leading source of knowledge about ecosystems and about societies. They are also highly unified advocates for societal change to confront ecological crisis. However, academics rarely turn to their own practices with the same transformational demands. Why shouldn’t biologists, sociologists, or, to take up my own case, art historians fundamentally alter how they work to do better with respect to what their own inquiries tell them about humanity and the planet?

In honor of Earth Day 2021, we are posting the video of a webinar Lynn Soreghan and I organized at OU two weeks ago as part of an international initiative led by Center for Environmental Policy at Bard College. At over 100 universities around the US and across the world local experts presented steps individuals can take to address the climate crisis.

Our own Oklahoma Climate Dialog was moderated by Lynn, and featured four speakers talking about what each of us can do to make a difference when it comes to climate.

(For more information about the speakers, see the event website. The webinar was sponsored by OU’s Mewbourne College of Earth and Energy, and the Environmental Studies Program in OU’s College of Arts and Sciences.)

An aspiration for the Solve Climate By 2030 project is that educators will devote class time to discussing climate change–under the rubric #MakeClimateAClass. To help with this effort the organizers at Bard have assembled a rich set of educational resources, including discussion templates for classes in a wide range of subjects. Other videos from this year’s series are being added to the Solve Climate By 2030 YouTube channel (you can also view videos from 2020’s dialogs). If you teach, our or another video might help get a discussion going in your class–and you might find one from your own state or country.

Our dialog did a great job of bringing into focus the question of how individual action bears on collective problems like climate change. Lynn and I will be back next week with some thoughts on that issue.

Vincent Desplanche, Sketches for a ‘Sentier Randocroquis’ at https://flic.kr/p/bhNYLM, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Vincent Desplanche, Sketches for a ‘Sentier Randocroquis’ at https://flic.kr/p/bhNYLM, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0[We welcome Robert Lifset to the blog, to comment on the talk by Dr. Joe Nation posted here last week. This post completes our series on Environmental Justice and Environmental Health.]

This is a tale of two bills. Continue reading

This spring we are offering a series of posts on the topic of Environmental Justice and Environmental Health. The series is organized in conjunction Continue reading

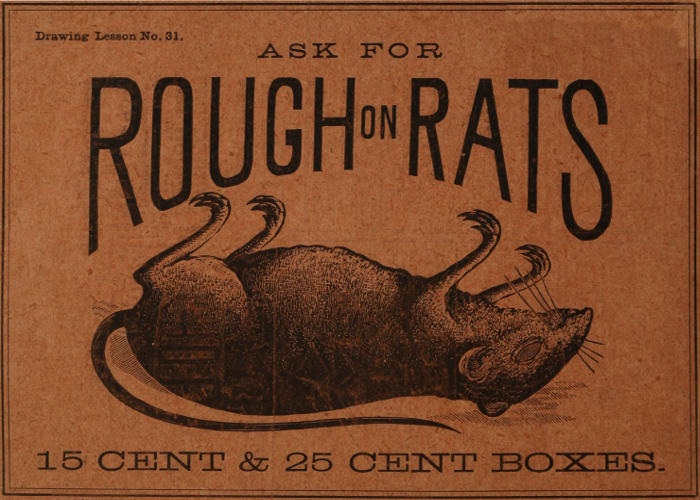

[This post completes a set of three on pesticides, part of our current series on Environmental Justice and Environmental Health. The others, by Jennifer Ross, include an overview of insecticides, and a talk on the impacts of insecticides in south Texas.] Continue reading

[This post completes a set of three on pesticides, part of our current series on Environmental Justice and Environmental Health. The others, by Jennifer Ross, include an overview of insecticides, and a talk on the impacts of insecticides in south Texas.] Continue reading

This spring we are offering a series of posts on the topic of Environmental Justice and Environmental Health. The series is organized in conjunction with Continue reading

[We welcome Jennifer A. Ross to the blog, to continue our series on Environmental Justice and Environmental Health. The video of her talk in the associated speaker series will available next week.]

People have a long and complicated relationship with pesticides. It starts with us defining what a pest is, and then seeking Continue reading

You must be logged in to post a comment.