Vincent Desplanche, Sketches for a ‘Sentier Randocroquis’ at https://flic.kr/p/bhNYLM, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Vincent Desplanche, Sketches for a ‘Sentier Randocroquis’ at https://flic.kr/p/bhNYLM, CC BY-NC-ND 2.0[We welcome Robert Lifset to the blog, to comment on the talk by Dr. Joe Nation posted here last week. This post completes our series on Environmental Justice and Environmental Health.]

This is a tale of two bills.

Sixteen years ago, Professor Joe Nation of Stanford University, then a Representative in the California Assembly, prepared two bills at the cutting edge of liberal reform in America.

The first, introduced in 2005, addressed health care. It included an individual mandate, electronic medical records, the creation of a center to study health outcomes and other cost saving ideas, many of which found their way into the Affordable Care Act (aka Obamacare). In many respects, this was a modest bill. It did not guarantee universal healthcare and it did not establish a single payer system.

The second, introduced in 2006, was an effort to address climate change. This bill created a mandatory state greenhouse gas (GHG) cap, a cap-and-trade system and a goal of reducing statewide GHG emissions to 1990 levels by 2020. This bill was far more ambitious.

The second, introduced in 2006, was an effort to address climate change. This bill created a mandatory state greenhouse gas (GHG) cap, a cap-and-trade system and a goal of reducing statewide GHG emissions to 1990 levels by 2020. This bill was far more ambitious.

Can you guess which bill passed? The climate change bill.

This is a strange inversion of the national experience where a cap-and-trade climate change bill passed the House of Representatives in 2009 (American Clean Energy and Security Act of 2009, aka Waxman-Markey) but was never brought to a vote in the Senate; and the Affordable Care Act was signed into law in 2010.

How are we to understand and make sense of the California experience? What does this reveal?

Professor Nation feels his health care reform effort came a little too early. The moment was not right. Democrats were (and perhaps still are) obsessed with a single payer system. Since healthcare accounts for eighteen percent of the economy, this reform took on powerful and entrenched interests who aligned in opposition to this reform.

The climate change bill utilized market mechanisms and there was a focus on the positive impact it would have on marginalized communities. Without elaborating, Professor Nation implied the political support provided by the environmental justice movement was important to creating momentum behind the bill. The climate bill was successfully framed as an effort to use technology to lower emissions and costs to everyone’s benefit.

And the plan worked. As this graph demonstrates, California succeeded in reducing its GHG emission to 1990 levels in 2016, four years early.

-

Slide from Dr. Nation’s talk

Slide from Dr. Nation’s talk

Professor Nation argues the climate change bill passed because there was strong public support, a strong economy in California and a strong Governor. In fact, at one point he claimed the Republican, Governor Schwarzenegger, was the “best Democratic Governor I ever worked with.” Yet without knowing the Governor’s position on healthcare, at least two of these conditions also existed for the health care bill.

Perhaps the bigger difference is that where the healthcare bill was specific and incremental, the climate change bill was simple and sweeping. The climate change bill was only thirteen pages. It simply stated a goal and left the job of implementation to the California Air Resources Board (CARB). And unlike with healthcare, there was no significant policy disagreement within the Democratic caucus on how to address climate change.

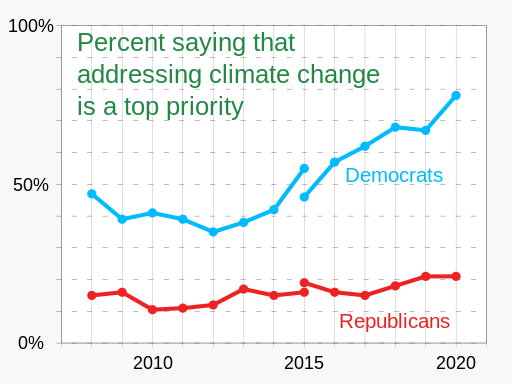

Which brings us to one all-important and obvious observation. California is a state dominated by Democrats. Professor Nation began his talk with a series of slides revealing opinion polls showing significant majorities of Americans supportive of government efforts to achieve universal healthcare and address climate change. Yet when you dig down into these polls and look at the disparity by political party affiliation these numbers reveal this support comes from large numbers of Democrats and small majorities or minorities of Republicans (i.e. on health care in 2019: 94% of Democrats and 40% of Republicans favor universal healthcare). If these issues teach us anything, it’s that strong public support is necessary for a major reform effort, but it’s not enough.

Which brings us to one all-important and obvious observation. California is a state dominated by Democrats. Professor Nation began his talk with a series of slides revealing opinion polls showing significant majorities of Americans supportive of government efforts to achieve universal healthcare and address climate change. Yet when you dig down into these polls and look at the disparity by political party affiliation these numbers reveal this support comes from large numbers of Democrats and small majorities or minorities of Republicans (i.e. on health care in 2019: 94% of Democrats and 40% of Republicans favor universal healthcare). If these issues teach us anything, it’s that strong public support is necessary for a major reform effort, but it’s not enough.

The attraction of incrementalism was through bipartisanship durable policy achievements could be realized. Yet the traditional means of achieving bipartisan support for a bill through compromise is effectively dead. Killed not just by partisanship but, on climate change, by the very refusal of Republicans to acknowledge the existence of the issue.

Which takes us back to the tale of two bills. In the mid-aughts California passed a sweeping climate change bill and rejected an incremental healthcare bill. Four years later, Washington passed an incremental healthcare bill and rejected a sweeping climate change bill.

This reveals that a liberal politics grounded in incrementalism began to fade in California before Washington. Few would deny that the Green New Deal is more ambitious than Waxman Markey or California’s climate change law.

The era of seeking bipartisan compromise and slowly making positive changes in an effort to address the challenges we face appears over. The costs of failing to achieve significant reform (on climate change and civil rights to name two) are steep and increasing.

Perhaps without intending to, Professor Nation taught us the era of incrementalism in liberal politics is over.

Robert Lifset is an associate professor of History in the Honors College at the University of Oklahoma.