[This post completes a set of three on pesticides, part of our current series on Environmental Justice and Environmental Health. The others, by Jennifer Ross, include an overview of insecticides, and a talk on the impacts of insecticides in south Texas.]

[This post completes a set of three on pesticides, part of our current series on Environmental Justice and Environmental Health. The others, by Jennifer Ross, include an overview of insecticides, and a talk on the impacts of insecticides in south Texas.]

Drawn from my book project Losing the Global War on Rats, a history of rat eradication and extermination in the age of the third bubonic plague pandemic (1890s-1950s), this post continues the conversation about toxic meanings and toxic substances started on this blog by Traci Voyles, Robert Bailey, and Jennifer Ross. Here, I explore the social debates and cultural meanings that followed one famous rat poison around the world.

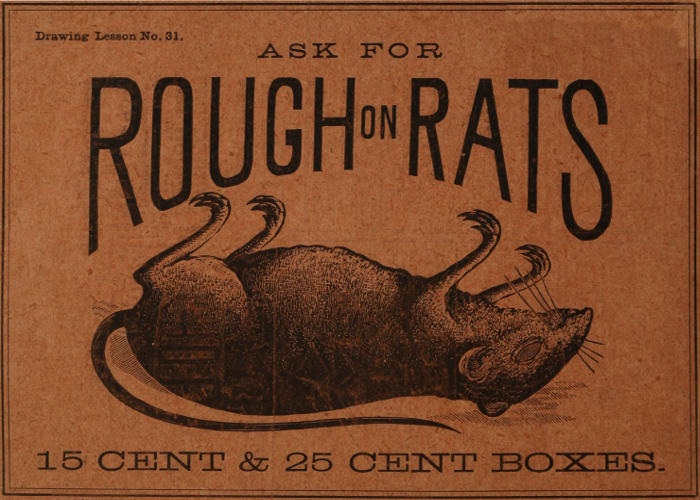

For centuries, Europeans used arsenic as rat poison. Randal Cotgrave’s 1611 French-English dictionary translated its English name “ratsbane” as the French mort-aux-rats (“death-to-rats”). The French phrase guerre aux rats (“war on rats”) also dates to the 1600s. The biologists, historians, and journalists who study human-rat relations call us “mirror” “twin” or “shadow” species, who have cohabited and coevolved for millennia. Thus, the human struggle to control rats dates to ancient times, but it was renewed after the 1600s with arsenic. Historians of chemistry and medicine James Whorton and Deborah Blum have documented the growth of a market for arsenic products in the 1800s, which included pigments, pesticides, and other consumer goods that normalized various household chemicals. Arsenic raticides had colorful names like “Scatter Rats” and “Rat Dynamite,” but the most prominent was the American “Rough on Rats,” (ROR) invented by New Jersey chemist Ephraim S. Wells (often E. S. Wells) in the 1870s. (For the rest of this post, I use “ROR” for the rat poison, and “rough on rats” for the brand name and catchphrase).

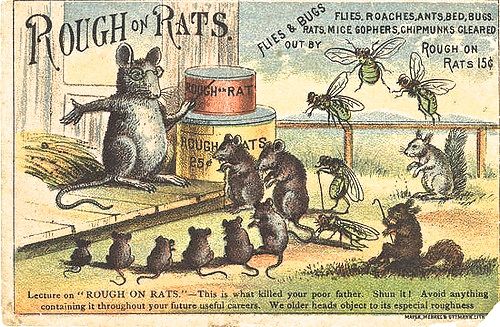

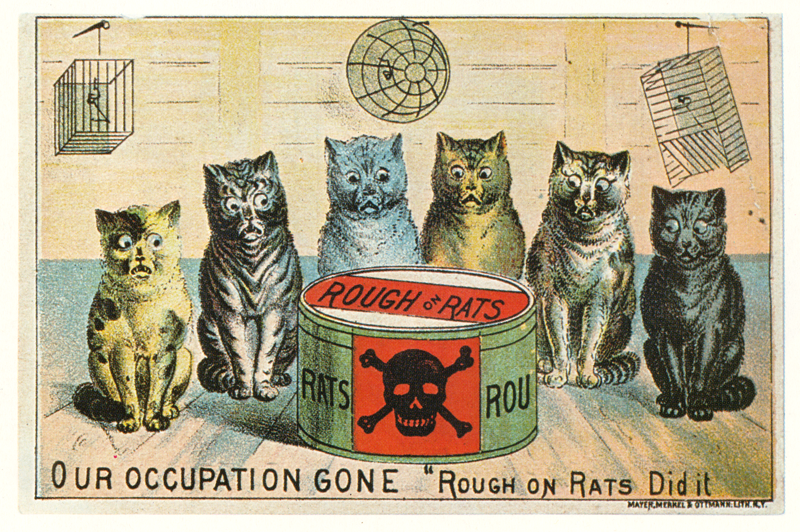

Wells also peddled patent medicines Rough on Corns, Rough on Itch, Rough on Piles, and Rough on Toothache (aka Rough on Dentists). He was known for aggressively advertising and trademarking these patent preparations. The Library of Congress conserves sheet music for the 1882 Rough on Rats jingle. He advertised in dozens of periodicals from Country Gentleman to Popular Science, but also pharmacy journals and the Merck report. The databases at Newspapers.com yielded over 82,000 hits for “rough on rats” from the 1880s to the 1920s, mostly ads. Wells also printed eye-catching illustrated trade cards, some ridiculous, some remarkable, and some racist.

Wells also peddled patent medicines Rough on Corns, Rough on Itch, Rough on Piles, and Rough on Toothache (aka Rough on Dentists). He was known for aggressively advertising and trademarking these patent preparations. The Library of Congress conserves sheet music for the 1882 Rough on Rats jingle. He advertised in dozens of periodicals from Country Gentleman to Popular Science, but also pharmacy journals and the Merck report. The databases at Newspapers.com yielded over 82,000 hits for “rough on rats” from the 1880s to the 1920s, mostly ads. Wells also printed eye-catching illustrated trade cards, some ridiculous, some remarkable, and some racist.

Authors wrote ROR into a range of American popular literature, including comic plays, poems, pulp novels, and crime fiction over half a century. Boston playwright Charles Townshend included ROR in four comic plays, and it appears in two Jack London works, the 1908 short story “That Spot” and the 1914 novel The Mutiny of the Elsinor. One of Wells’s 1891 ads claimed, “‘Rough on Rats’ is sold all around the world, in every clime, is the most extensively advertised and has the largest sale of any article of its kind of the face of the earth.” An 1892 ad claimed that Wells spent $70,000 a year promoting ROR. He became famous in advertising journals, in scientific journals, and in public debates about how to safely regulate, label, and sell patent preparations, especially ROR. Contemporaries noted the product’s global reach, sold in the U.S., Canada, Mexico, the Caribbean, and northern South America, but also distributed by depots in Paris, Marseilles, Alexandria, Cairo, Cape Town, Bombay, Hong Kong, Shanghai, Sydney, and Hawaii. Around 1900, it was the world’s most visible rat poison thanks to a torrent of text and images.

•

Having rounded the world, ROR provoked controversy everywhere concerning its possible human harms: suicide, murder, and accidental ingestion. Critical editorials, written in both popular newspapers and professional journals for chemists, dentists, doctors, pharmacists, and veterinarians, amplified and cited each other across the English-speaking world, including Britain, the U.S., Canada, India, Australia, and New Zealand. Detroit medical journal Therapeutic Gazette called ROR “a needlessly cruel minister of the angel of death.” The Auckland, New Zealand Observer wrote, “‘Rough on rats’ is becoming ‘rough on men,’” while the Christchurch Star predicted “a long list of human victims.” Canadian critics in Montreal included surgeon J. Baker Edwards, coroner Wyatt Johnson, and veterinarian Wesley Mills, who warned against accidentally poisoning pets in his 1891 dog-training manual. In the 1880s and 1890s, doctors debated how to treat arsenic ingestion (usually with an emetic), while journalists and lawmakers debated how to label poisons and regulate their sale. While journalists often cried “suicide epidemic” to make headlines, medical professionals, for example at the British Medical Journal, warned against overusing this inflated and inflammatory term. New Zealanders debated the failings of their colonial hospital system, while the newspaper Clutha Leader caustically joked that the politicians responsible should take ROR.

I surveyed New Zealand’s debate about ROR at their national library’s accessible digitized historical documents website Papers Past. Two recent local history projects (here and here) have also interpreted these sources. What strikes me is that ROR became a focal point, a catchphrase or tag, for a heated debate touching on a range of interrelated issues: health care, suicide, pest control, alcohol/ism, “melancholy” (today’s depression), consumer safety, the media’s suggestive power, and most broadly socioeconomic conditions in this far-flung British colony. The quantity of words and vitriol spilled about ROR was out of proportion with the substance’s actual impact. New Zealand vital statistics show that deaths from ROR were a tiny fraction of all deaths. Between 1879 and 1885, when ROR debate was thriving, New Zealand suicides ranged from 34-50 men each year and 4-10 women; only some of these were poisonings, only a portion of poisonings were from arsenic, and only a handful of arsenic poisonings were from ROR. In 1887, New Zealand vital statistics first mentioned ROR by name, while they diagnosed a suicide problem in Australia and New Zealand: “The deaths from suicide are in about the same proportion to the population of New Zealand as in New South Wales and South Australia. They are proportionally about 50 per cent. more numerous than in Tasmania, but considerably less numerous than in Queensland or Victoria. Suicidal deaths are proportionately much more numerous in all the Australasian Colonies, with the exception of Tasmania, than in England.” New Zealand newspapers, meanwhile, reported on alleged “suicide epidemics” in Vienna, St. Petersburg, and New York, in brief and relatively sensational stories.

Beyond New Zealand, British colonists used ROR in Rhodesia, Zanzibar, Egypt, and India. The poison’s colonial context was clear to the Notre Dame student paper the Scholastic, which included ROR in a 1900 comic allegory of students fighting rats in Brownson Hall (demolished 2020) as a Dutch colonial rat war in the Transvaal during the Second Boer War. ROR also left a trail in British India. In 1889, Police Sergeant J. F. Matthews, on special duty at the Calcutta Coroner’s Court, committed suicide by taking a whole box of ROR, scrawling a farewell note in his pocketbook, and then hitting the town for some light mayhem before turning himself in to the hospital where he died around 3am. In 1905, Calcutta doctor Dokari Ghosh criticized British use of ROR for controlling rats during India’s long and deadly bout of bubonic plague amid the third pandemic. The following year, the newspaper Indian Spectator wrote, “Governor-General in Council is very rough on rats: he does not tell us, however, how the rodents may be killed.” Besides criticizing British rat- and plague-control measures, as Ghosh had, this quote illustrates how “rough on rats” became an adjective used around the English-speaking world to describe people or situations.

In 1903, a guide to American slang said that “rough on rats” meant any hard case or tough situation. A 1908 story about circus performers in fitness magazine Physical Culture said, “the circus life must surely be ‘rough on rats.’” A 1914 lip-reading training guide for the deaf suggested the phrase “Rough on rats had better be bought to rid us of these pests” to practice the letter R. In 1933, James Thurber titled his New Yorker portrait of flamboyant Louisiana governor Huey Long “rough on rats,” while Van Beuren studios released an animated short film with the same title, in which three kittens battle a giant rat and win.

I haven’t yet watched the 1913 British film, or read Williams Francis’s 1942 detective novel. By the 1950s, a scholar of the Spanish language noted that the phrase was used in American Spanish. Since the 1880s, the phrase born from Wells’s prolific advertising had matured into an everyday English phrase used from New Zealand to India and New York. “Rough on rats” described athletes, detectives, and politicians—rough, tough, and manly stuff, and usually complimentary.

•

ROR was pervasive in global shipping, for example at the Suez and Panama Canals. With ROR depots at Alexandria and Cairo, it is fitting that Egyptian scholar Muhammad Kasim’s 1897 Idioms of the English Language for Arabic speakers translated “rough on rats” as samm al-fa’r, meaning arsenic or rat poison. I read this translation as both a warning to readers, because Wells’s brand name was euphemistic, and an acknowledgment that Wells’s brand was dominant enough to stand in for all rat poisons. Similarly, in 1921, the U.S. Public Health Service required that ROR suicides be officially reported as “suicide by arsenic.” Together, these two examples show that the brand name’s transformation into an everyday expression hid a danger: that consumers might not recognize it, or officials might not record or report it, as poison. This concern reached back to ROR’s debut in the 1880s. Wells released ROR ads in 1908 with the slogan “the government uses it,” claiming that the U.S. Public Health Service bought 3,600 boxes for use at the Panama Canal because ROR was “reliable” and “unbeatable.” A 1909 document from Panama’s sanitation department accounts for 442 boxes, but no more. Around the same time, American memoirist in Panama Mary Chatfield wrote, “I have fixed rough on rats with sugar and laid poisonous powders about, but all to no purpose.” The mice and roaches she aimed to kill mocked her, playing “tag” by night and using her dresser as a “hotel.”

Wells’s ads had long promoted ROR for killing many creatures besides rats: mice, flies, bedbugs, ants, roaches, mosquitoes, potato bugs, moths, and water-bugs, but also moles, chipmunks, “sparrows, jackrabbits, squirrels, and gophers.” This long list of potential targets both sold ROR as a universal pest control solution, and also more subtly signaled that arsenic was deadly for many living things. Ornithologist Franklin Lorenzo Burns reported in 1926 that he used ROR to taxidermy a short-eared Owl. In 1923, Singapore’s chief medical officer A. L. Hoops wrote, “Man is a combative animal. Let every man, woman, and child, make war on disease and its carriers; be rough on rats; and give no quarter to flies and fleas, mosquitoes and lice, the insect carriers of infection.” As others had done before him, Hoops let the literal and figurative meanings of “rough on rats” resonate together.

Wells’s ads had long promoted ROR for killing many creatures besides rats: mice, flies, bedbugs, ants, roaches, mosquitoes, potato bugs, moths, and water-bugs, but also moles, chipmunks, “sparrows, jackrabbits, squirrels, and gophers.” This long list of potential targets both sold ROR as a universal pest control solution, and also more subtly signaled that arsenic was deadly for many living things. Ornithologist Franklin Lorenzo Burns reported in 1926 that he used ROR to taxidermy a short-eared Owl. In 1923, Singapore’s chief medical officer A. L. Hoops wrote, “Man is a combative animal. Let every man, woman, and child, make war on disease and its carriers; be rough on rats; and give no quarter to flies and fleas, mosquitoes and lice, the insect carriers of infection.” As others had done before him, Hoops let the literal and figurative meanings of “rough on rats” resonate together.

As I work to interpret this remarkable archive of literal and figurative uses of “rough on rats,” I am struck by how these uses intertwine. On one level, there is a literal history here of arsenic rat poison and the people harmed by it, which became a surprisingly prominent social issue. On a more symbolic level, though, the phrase “rough on rats” took on life of its own through a thick stock of literary references, printed advertisements, cute animal images, and global English slang, which lent the phrase valences of meaning: athletic, colonial, masculine, and military. Although I have more work to do in interpreting this archive, I hope for now that this post illustrates the cultural work that normalized ROR as an everyday commodity, a global icon, and a health risk, while its brand name became a way to compliment or insult people for their “roughness.”

Peter S. Soppelsa is an assistant professor in the Department of the History of Science at the University of Oklahoma.

![All this trouble might have been avoided by use of one fifteen cent box of 'Rough on Rats.' [front]](https://live.staticflickr.com/8357/8384584514_373b12d746_n.jpg)

I really enjoyed your post. It made me think of the Raid bug spray commercials from when I was a kid, and the idea that Raid was so tough on bugs they exploded. Using Raid (at the time strong OP pesticides) made you tough (on bugs). The cartoonish bugs were so like the rat in the Rough on Rats cartoon. It’s interesting how these products and advertising affect us. I keep thinking of blood thinners as rat poison not arsenicals and needed the reminder. I wonder if there are similar ads for the blood thinner style poisons.

I also wanted to let you know that in our pesticide inventory the blood thinner-based rat poisons were quite common in homes in the colonias. There were even some places in Texas putting out rat poisons to kill feral hogs (this was shockingly unconcerned about other animals). I can see the equivalence of rat poison so strong it will take out a hog.

Thanks for your comment. I see so much useful overlap between our research. The new generation of rat poisons after WWII is significant, including ANTU, 1080, and warfarin, which was a rat poison before it was adapted as a human blood-thinner. I have looked at some printed advertisements from Du Pont for ANTU and Monsanto for 1080, during the early Cold War, which used the atom-age idea of “mass destruction” to show how rough and tough their poisons were. I need to find more ads for Warfarin/D-Con; the ones I have seen are are slightly gentler than ads for other poisons, but not by a wide margin. Apparently, the warfare/warfarin pun was deliberate.