In 2016, the Oklahoma Energy Resources Board (OERB) published the fourth volume of its “Petro Pete” series of illustrated children’s books. To promote Petro Pete’s Big Bad Dream, K-2 classes throughout the state were invited to enter a contest that October. Participating teachers agreed to read the online version of the story to their classes and then to post to the OERB’s Facebook page photographs with “the students holding their favorite petroleum by-products (sic) from their home or school.” The winner was determined by the number of online “likes” and a review of the photo by OERB judges. Submitted by a class in Tulsa, the winning entry shows 20 first-graders on their school’s playground posing with a variety of prized items: three footballs, several backpacks, a clear bag of candy, a dog leash (or maybe a belt), a basketball, stuffed animals of various species, a plastic bottle that might be shampoo, a toy car, and a pair of sunglasses. To aid the students’ selections, the contest guidelines included a list of 97 familiar items that are manufactured with petroleum ranging from backpacks and balloons to wax and volleyballs. For winning, the students received a celebratory visit to their class by two state legislators accompanied by the OERB’s costume mascot Petro Pete. During the visit, the elected officials led them in another round of story time, reading them Petro Pete’s Big Bad Dream as the students followed along in their complimentary hardcover editions.

In addition to the language arts preparation from reading the book, the contest guided the students to enact the moral of the story by making a connection to a valuable possession. Petro Pete’s Big Bad Dream begins with Pete reading in bed about oil and natural gas. He falls asleep wondering what “life would be like if we didn’t have petroleum,” and then he wakes to that reality. When his mom knocks on his door to rouse him for school, he looks around to find that many of his things are missing. Without a tooth brush, comb, or his usual clothes, he heads outside to wait for the school bus in his pajamas. Deprived of gasoline, wheels, plastic components, and much else, the bus does not arrive. Without tires and a seat, Pete’s bike leans unhelpfully against the garage door. Forced to walk, he arrives at school just in time. His teacher, “Mrs. Rigwell,” reviews the previous day’s lesson with the promise of explaining the mystery of Pete’s situation. Another student, Nellie, recalls learning that petroleum is a source of energy composed from animals and plants that inhabited Earth millions of years ago. Pattie explains that derricks are machines engineered to drill for petroleum underground. Mrs. Rigwell concludes the review session by announcing that after lunch and recess they’ll have a new lesson on the work of refineries.

During the break from class, Pete’s misfortune persists and affects his classmates. A milky substance spills unfrozen from an ice cream dispenser that lacks refrigeration. On the playground, storage boxes are empty of footballs, basketballs, and soccer balls. When the students return, Mrs. Rigwell creates a chart on the board to describe how crude oil extracted from the earth is refined to manufacture different kinds of products. On a day they’re disappearing, they seem especially necessary. At the end of the school day, the narrative shifts to reveal that Pete has, of course, been asleep for this whole story. The sound of the school bell is actually his morning alarm. Released from the big bad dream, he leaps from bed excited that his things are restored. After dressing in his signature overalls, hard hat, and goggles, Petro Pete exclaims to his dog, “Repete! That was all a dream! All of my petroleum by-products are back.” On the final page, Pete smiles and waves from the back of the OERB school bus as it drives away from his home. His experience has taught him that he is always using petroleum; it is integral to most things he needs and enjoys. The additional, unsubtle inference to take from Pete’s dream is that we should feel excitedly grateful to be the beneficiaries of the oil and natural gas industry. In the story, no other emotions are associated with the extent of our dependence on petroleum.

This fourth installment in Petro Pete’s positive experiences with oil and natural gas became a topic of interest for investigative journalism into the OERB’s involvement in Oklahoma’s schools and the similar influence of oil industry advocacy groups in other states. The Center for Public Integrity in Washington D.C. and National Public Radio’s State Impact Oklahoma partnered for Jie Jenny Zou and Joe Wertz’s exposé “Oil’s Pipeline to America’s Schools,” which was published online by both organizations on June 15, 2017. An abridged version appeared the same day in The Guardian, and Wertz’s radio report focusing on just the OERB was broadcast by NPR affiliates in Oklahoma. Each version begins with an anecdote about the fall 2016 Petro Pete book tour. The reporting correctly identifies the OERB as a non-profit agency that was founded by the state legislature in 1993 but is funded entirely by voluntary contributions from oil and natural gas companies. The agency has a dual mandate, and is legally bound to commit half of its annual spending to the first objective of cleaning up abandoned oil-wells and promoting well-site safety. Oklahoma residents with access to television will be familiar with the OERB’s public service commercials urging children not to play on well-sites. The second charge, as stated on the inside cover of Petro Pete’s Big Bad Dream, is to “educate Oklahomans about the vitality, contributions and environmental responsibility of Oklahoma’s oil and natural gas industry.” Since the introduction in 1996 of its first curriculum for teachers, “Fossils to Fuels,” the OERB has addressed this second objective with increasing involvement in primary and secondary schools. Zou and Wertz report that OERB curricula are used in 98% of the state’s school districts. The OERB Homeroom website displays a running count of teachers who have completed a workshop to prepare them to offer interactive, grade-level appropriate STEM lesson plans; as I write, the total is up to 16,621. Completing the training also provides teachers with free materials to use for science exercises in their classrooms, access to password-protected online content and lesson plans, and eligibility for funding to support class field trips.

This fourth installment in Petro Pete’s positive experiences with oil and natural gas became a topic of interest for investigative journalism into the OERB’s involvement in Oklahoma’s schools and the similar influence of oil industry advocacy groups in other states. The Center for Public Integrity in Washington D.C. and National Public Radio’s State Impact Oklahoma partnered for Jie Jenny Zou and Joe Wertz’s exposé “Oil’s Pipeline to America’s Schools,” which was published online by both organizations on June 15, 2017. An abridged version appeared the same day in The Guardian, and Wertz’s radio report focusing on just the OERB was broadcast by NPR affiliates in Oklahoma. Each version begins with an anecdote about the fall 2016 Petro Pete book tour. The reporting correctly identifies the OERB as a non-profit agency that was founded by the state legislature in 1993 but is funded entirely by voluntary contributions from oil and natural gas companies. The agency has a dual mandate, and is legally bound to commit half of its annual spending to the first objective of cleaning up abandoned oil-wells and promoting well-site safety. Oklahoma residents with access to television will be familiar with the OERB’s public service commercials urging children not to play on well-sites. The second charge, as stated on the inside cover of Petro Pete’s Big Bad Dream, is to “educate Oklahomans about the vitality, contributions and environmental responsibility of Oklahoma’s oil and natural gas industry.” Since the introduction in 1996 of its first curriculum for teachers, “Fossils to Fuels,” the OERB has addressed this second objective with increasing involvement in primary and secondary schools. Zou and Wertz report that OERB curricula are used in 98% of the state’s school districts. The OERB Homeroom website displays a running count of teachers who have completed a workshop to prepare them to offer interactive, grade-level appropriate STEM lesson plans; as I write, the total is up to 16,621. Completing the training also provides teachers with free materials to use for science exercises in their classrooms, access to password-protected online content and lesson plans, and eligibility for funding to support class field trips.

For Zou and Wertz, the discrepancy between the underfunding of public schools caused, in part, by reductions to state appropriations for education and the OERB’s generous resources is a recipe for schools and teachers under strain to accept materials that “paint a rosy picture of fossil fuels in America’s classrooms” and send “mixed messages” about climate change. Two satirical television news programs that followed up on their exposé were more harsh.

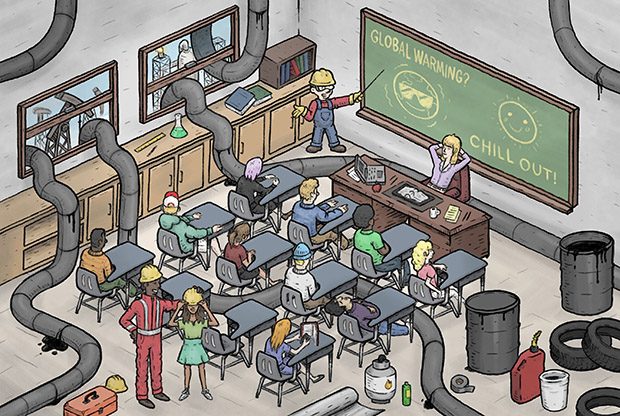

Jordan Klepper’s The Opposition on Comedy Central targeted the OERB as a propaganda operation. In its segment “Thanks, Big Oil, for Teaching Oklahoma’s Kids,” comic field reporter Laura Grey goes on location in Oklahoma City to uncover the truth behind the state’s school funding crisis as well as the prospect that the oil and natural gas industry could save education in the state. Newsbroke, an online production of Al Jazeera, ran a longer segment on “How Big Oil Brainwashes Kids” that associates the OERB more pointedly with the chief strategy of climate change denial: fomenting doubt. The show’s host links the Petro Pete books and videos by the “Bill Nye knock-off” Professor Leo to recent legislative efforts in several states to require schools to “teach the conflict” about climate change.

Punching up at the powerful oil and natural gas industry, the investigative report and satirical videos characterize the OERB as another agency spreading misinformation in concert with those companies, industry advocacy groups, conservative think tanks, and elected officials that Naomi Oreskes and Erik Conway labeled Merchants of Doubt. Published in 2010, the book documents the extensive, coordinated strategy to counter the scientific consensus on climate change not with refutation but instead by promoting the idea that the agreement is hype, the experts are conflicted, and that reasonable people must wait and see what surety further research will provide in due time. Pitched in defiance of a preponderance of evidence, the publicity campaigns Oreskes and Conway identify pretended perfect certainty is the measure of scientific veracity, making “due time” interminable. Their findings were amplified in 2015 when Inside Climate News’ eight-part investigative report, “Exxon: The Road Not Taken,” revealed that Exxon conducted “cutting-edge climate research decades ago and then, without revealing all it had learned, worked at the forefront of climate change denial, manufacturing doubt about the scientific consensus that its own scientists had confirmed.”

The involvement of oil and gas corporations in funding the transmission of science curricula to primary and secondary schools would seem to invite associating the OERB with other discredited campaigns to encourage skepticism about the scientific consensus. I want to suggest that this is a mischaracterization. The satirical videos, in particular, ridicule the OERB selectively and neglect that its teaching materials are both popular with many teachers and created in consultation with committees of educators. The curricula for students correspond to the Oklahoma State Department of Education’s Academic Standards, and the relevant learning objectives are reprinted with the OERB’s lesson plans.

My point, however, is not to suggest that the OERB isn’t implicated in climate change denial. The story it tells to students may be right about the precious utility of petroleum products, but by itself that message fails to acknowledge that the majority of fossil fuels will end up in the atmosphere and not in plastic toys. Instead of disseminating doubt, OERB contributes to climate change denial by diminishing the significance of global warming with inattention, while at the same time providing otherwise legitimate content, resources, and assistance to educators across Oklahoma. In other words, OERB manages to advance the neglect of anthropogenic climate change while maintaining a seemingly plausible denial of such irresponsibility. With this approach, the OERB’s outreach to schools introduced in 1996 anticipated a shift in strategy for climate change denial that has emerged into prominence more recently.

Last month, the Community Interest Company Influence Map issued a report on “Big Oil’s Real Agenda on Climate Change.” The group found that since the COP 21 Paris Accord, the five largest publicly-traded oil and natural gas companies – BP, Dutch Shell, ExxonMobil, Total, and Chevron – have together spent $1 billion on lobbying against environmental regulations and on publicity campaigns to rebrand them as responsible stewards of the environment who are indeed expert in the reality of anthropogenic climate change. Considering the ICN’s series, Exxon’s approach is especially galling. Even as the company denies the veracity of ICN’s reporting, which was derived from studying the company’s own documents and interviewing scientists who conducted the research in the late 1970s, Exxon now boasts that it has been at the forefront of innovative climate change research for 40 years. This is somewhat true, but perversely so since for years Exxon provided policy-makers and the public misinformation while hiding its research findings. According to the Influence Map report, the five corporations’ actual investment in de-carbonization technologies and alternative energy research is minimal when measured against their recent spending to accelerate the extraction of fossil fuels. The scale of the difference is so disproportionate that public relations campaigns to promote the companies’ new green identities would also be risible were they not so expensive.

Just wanted to give some context on power generation in the United States. This graph (data from Wikipedia) shows electrical power generation in the United States, lines are drawn to extrapolate. Solar does not include distributed systems (e.g. solar panels on one’s home); currently that would add about 0.7%. Hydroelectric is near 10% and nuclear is about 20%. On this scale, use of gasoline for transportation fuel would be about 45% and that number has been pretty flat over this time frame. I wanted to restrict this post to the United States, but electricity percentage in the world generated from fossil fuels is about the same.

In principle, the technology exists today to eliminate almost all liquid fuel needs in the United States, i.e. use all electric vehicles. The cost for a battery powered car is around $10,000/vehicle. The average lifetime of a car is 150,000 miles or 8 years. The average cost to fill a car with gasoline for a year is about $1500 ($2.50 gallon of gas assumed). The average cost to charge an electric car is ~$550/year at current electricity rates in the US. So ignoring the time value of money, a pretty minimal gas tax would make the electric car cheaper to buy over the lifetime of the car assuming no changes in any of these dollar figures.

However, if the US did this, then the question is how are we going to generate the extra ~45%* of electricity to power these cars? I will say it this way… I have yet to see any plan that could realistically (defined as having no blackouts and no really high reductions in power usage) come anywhere near changing the slope of the gray line, or that could be used to generate the extra 45% of the power required for electric cars, that doesn’t have nuclear energy as the primary power source. So, unless we adopt nuclear, I believe we must use fossil fuels for most of our power generation.#

Finally, I do recognize the many simplifications made in this analysis. What about the energy required to make a battery as opposed to a gasoline engine? How many batteries are recycled? Batteries require certain very specialized metals; how will increasing the number of batteries affect this supply? This analysis also ignores conservation efforts (power usage in the US has been pretty flat over the last ~15 years even though our population has increased) as well as possible breakthroughs in technology (I see incremental improvements in solar occurring, but nothing on the 10-20 year horizon that I think will really change anything I have said here).

*The 45% includes all efficiencies. The gasoline engine is about 20% efficient (about 20% of the inherent energy that is released by combusting gasoline is used to power the car). Including the energy cost of producing the gasoline and getting it into your gas tank makes that number about 18%. How efficient is an electric car? About 60% of the electricity that flows into your car powers the car, i.e. 3 times a battery is 3x as efficienty as a gasoline engine in powering your car. There is about a 10% line loss on average getting the electricity to your car. Other than hydro, all power plants are about 40% efficient. Hence, to a first approximation, the 45% is about right since all factors considered the efficiency of both a gasoline and electric engine are 20% currently. The only exception is hydroelectric power where the 45% on that scale should be 25% because hydroelectric power is much more efficient to generate.

#If we increased our natural gas generation to come up with 45% more power, there would be a net reduction of about 25% in our CO2 emissions because natural gas emits about 25% less CO2 for the same power generation as gasoline. If we increased power generation with coal, we increase our CO2 emissions by 25% vs. burning gasoline.

So I happened to be in Dallas recently, and I visited the Perot Museum of Nature and Science, which is actually pretty impressive. One of the permanent exhibits is dedicated to energy (the Tom Hunt Energy Hall)–and it followed the pattern you describe here precisely. That is, it did not engage in any outright climate denialism, but it simply did not address the issue of CO2 emissions at all. It is not that the exhibit ignored all externalities associated with energy production . . . it briefly mentions controversy associated with fracking. And there are display cases presenting (in favorable terms) alternative energy sources–indeed, the header image for the exhibit web page features wind turbines! But the most text heavy portion of the exhibit is a set of arguments about why petroleum should remain a principle energy source. Unless I missed it, I don’t think there is a single mention of climate change to be seen: a visitor can learn a whole lot about oil and gas exploration, and the energy industry, and encounter no suggestion that there is a connection to be made here.

I should add–there are other exhibits in the museum (on other floors) that cover the implications of climate change for biodiversity. And regarding another controversial scientific topic–evolution–the museum has some excellent displays, including on human origins.

Since my piece on Petro Pete was posted to Inhabiting the Anthropocene on April 10, there has been a modest flurry of news reporting that is relevant to the topic.

First, NPR has publicized the results of an NPR/Ipsos survey conducted in March 2019 that found 80% of people, 84% of parents, and 86% of teachers agree that climate change should be taught in schools:

https://www.npr.org/2019/04/22/714262267/most-teachers-dont-teach-climate-change-4-in-5-parents-wish-they-did

The poll also found that fewer than half of parents and teachers report communicating with their children or students about climate change. The linked article summarizes the report and notes that several factors explain teachers’ downplaying or excluding the topic, including limited resources and higher priorities for instruction in many disciplines. The latter part of the article covers the availability and use of climate change curricula from the Next Generation Science Standards and, in contrast, ongoing efforts in several states to pass legislation that would block or confound the teaching of anthropogenic climate change.

Second, as a follow-up to the NPR/Ipsos survey, on April 23 the radio show 1A broadcast on NPR stations nationally a program on “Teaching Climate Change: Push and Pull.”

https://the1a.org/shows/2019-04-23/how-are-we-preparing-the-next-generation-to-fight-climate-change

The show’s host Joshua Johnson interviews a high school science teacher, two executives from non-profit organizations dedicated to responsible science instruction in schools, and an academic professional whose research concentrates on science education. One of the panelists shares that 19 states and the District of Columbia have so far adopted the Next Generation Science Standards. “Petro Pete” is discussed starting at 38:50 in the archived version of the program.

Finally, on April 25-26 NPR stations in Oklahoma broadcast State Impact Oklahoma’s report on a new initiative to assist schools in teaching about renewable energy. Two retired teachers partnered with the Sierra Club to develop an alternative to the OERB’s programs. The founders of the Oklahoma Renewable Energy Education Program (OREEP) indicate that more than 100 Oklahoma teachers have completed a training workshop and that approximately 10,000 students have been introduced to their curricula.

https://www.kgou.org/post/teachers-create-renewable-energy-curriculum-compete-oerb

I’d also like to thank Zev and Brian for their replies to the post.

Zev’s account of the Tom Hunt Energy Hall corresponds to the speculative point I introduce in the conclusion of my blog post, which is that industry-sponsored climate change denial is continuing but that new rhetorical modes are emerging. Aside from the Trump Administration’s farcical repetition of conspiracy theories about the source of the scientific consensus, the project of denying the reality of climate change by promoting perpetual doubt is finally exhausted. Zev reports noticing in the exhibition bona fide instruction about energy along with a significant absence of reference to anthropogenic climate change. I’m reminded that as a youngster in Catholic school, I was taught that significant omissions could also be sins. OERB’s curricula would have Oklahoma’s school children regard abandoned well sites as the unintended grave danger that has resulted from oil and natural gas production. In other words, “Petro Pete” stories are a narrative filibuster to occupy classes with energy topics that omit the observation that burning fossil fuels is a primary cause of global warming.

Brian’s calculation of the best-case scenario for reducing dependence on fossil fuels – without a major turn to nuclear, they’ll remain the majority source – strikes me as an impressive quick rendering of energy at work. I appreciate the time and expertise that went into the reply, which I’d like to read as a thought exercise about how to meet current energy demands with the least possible reliance on fossil fuels. Such thinking is necessary for fair consideration of nuclear. It’s relevant for carbon capture objectives. And it could inform open-eyes reckoning with increasing heat. Nothing I’ve read in scholarship and journalism on the operations of fossil fuel corporations in regard to climate change indicates that they are similarly engaged in devising utilitarian, ethical scenarios that accept the value of minimizing carbon emissions while striving for balance with the rival value of not destabilizing social life with potentially harmful energy scarcity.

I also want to push back on the suggestion that an account of the necessity of fossil fuels for the foreseeable future simply adds context to my blog entry. It’s obviously relevant context for the collective effort of Inhabiting the Anthropocene. However, as an immediate follow-up to a post that faults oil and natural gas corporations for bad acts, it can be read as a departure from my topic, which is not the plausibility of alternatives to oil and natural gas. Prompted by the specific example of the OERB’s Petro Pete curriculum for elementary schools in OK, the general concern of my post is oil and natural gas corporations’ strategic contributions to the discourse of climate change denial. The fact that some degree of dependency on fossil fuels is a virtual certainty in the coming decades does not excuse those corporations’ sponsorship of misinformation campaigns about anthropogenic global warming.

Jim, I appreciate the detailed feedback and agree; we need to teach everyone about global warming and the environmental cost of burning fossil fuels (and Zev, for a museum to not mention that is not appropriate in my opinion). All energy sources have disadvantages, and we need to openly discuss tradeoffs between different energy sources. We also need to discuss tradeoffs regarding a carbon tax, conservation etc. Whether it is corporate responsibility to talk about negative aspects of the energy source they are making/promoting (and all energy sources have negative aspects to varying degrees) is a hard question to answer for me personally, I would probably say no. Certainly though in my opinion, corporate responsibility does not allow for lying and corporate misrepresentation of facts should (and I believe is) a crime.

As Jim knows, I’ve done some research on OERB, EnergyHQ.com, etc. related to this topic for my class Environment and Society (GEOG 3443), and have given a few talks on it at the American Association of Geographers meetings and in the Dept. of Geography and Environmental Sustainability here at OU.

If anyone is interested, a former student of mine just came across a journal article in the Taylor & Francis journal Environmental Education Research that might be of interest – it talks about this topic in the setting of Saskatchewan, “Petro-pedagogy: fossil fuel interests and the obstruction of climate justice in public education”: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/13504622.2019.1650164. And, there’s a book written by a University of Wyoming professor, Jeffrey Lockwood, called “Behind the Carbon Curtain: The Energy Industry, Political Censorship, and Free Speech” that details what’s going on in Wyoming, which includes providing school curriculum to “enhance the workforce pipeline and promote general energy literacy among all students.” https://unmpress.com/books/behind-carbon-curtain/9780826358073. Cheers!