Empty classroom. Photo by Benson Kua (CC BY-SA 2.0)

The Dream Course, Interrupted

With the end of the spring semester, the Climate Change in History Dream Course came to a close. The course was neatly broken in two by COVID-19, which was officially declared a pandemic in mid-March, just as we were wrapping up classes for Spring Break.

Until that point, the Dream Course proceeded as planned, with richly rewarding campus visits and public lectures from historians Gregory Cushman and Deborah Coen, and sociologist Kari Norgaard. We learned so much from these visits. We were grateful for terrific turnouts at their public lectures and excellent discussions with our students during their classroom visits. On this blog, faculty colleagues from OU provided reflection and commentary that further embellished and enriched our conversation. Our thanks go out to Brian Burkhardt, Scott Greene and Bruce Hoagland, Lynn Soreghan, Brian Grady, and Laurel Smith.

Special thanks are due to my co-instructor Dr. Suzanne Moon and our TA Aja Tolman. I also want to recognize our department administrator Sam Fellows, so capable with arrangements for travel, logistics, and finances. Finally, I thank our department chair Hunter Heyck, who first encouraged us to apply for the Dream Course and helped prepare the application. The course was a team effort from the beginning and our local community—centered on the History of Science Department and the faculty group behind this blog—provided invaluable support.

*

One of the intellectual refrains of this course was the question of why more people don’t see climate change as a present and urgent problem to be solved now, rather than a disaster predicted or projected to happen at some future time. Although we perhaps fancied ourselves above this problem—after all, we and our students had chosen to study climate change for the semester—I realize in hindsight how much the risks of climate change remained, for our class, largely in the realm of prediction and projection. Even as we repeated, again and again, that those risks are present here and now, they did not seem to touch our classroom itself, or to hit home in very concrete, local, and individual ways.

But the sudden interruption of COVID-19 changed all this. In mid-late March, as we scrambled alongside colleagues across academe to move our course online, we also faced a half-finished public event series, with three of our six scheduled guest speakers, along with ourselves and our students, stuck at home. This blog has provided us the space we needed to continue the Dream Course’s public-facing mission in an academic environment suddenly oriented around video conferencing. Thanks to generous assistance from Zev Trachtenberg, our final three guest lectures from Clark Miller, Candis Callison, and Paul Edwards are available to watch online via this blog.

Photo by Damien Bakarcic (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Health in the Anthropocene

Because none of our guest speakers highlighted the health risks of climate change, I made this the focus of my last several lectures for the semester. Preparing for these lectures made clear two things: first, that thinkers are already connecting COVID-19 with the human-made environmental changes of the Anthropocene; and second, that the health impacts of anthropogenic environmental change are particularly useful examples for illustrating that the impacts of anthropogenic environmental change demand urgent action now.

When Johan Rockström et al. called for a “safe operating space for humanity,” or when New Yorker science writer Elizabeth Kolbert reminded us that the sixth extinction’s assault on biodiversity was an existential threat to humankind, they were talking about the risks to human health and safety posed by the Anthropocene. Although we often hear that the Anthropocene poses “existential threats” to humanity, this phrase often evokes a coming apocalypse, a deferred disaster, rather than an ongoing crisis. This crisis poses health and safety risks for humans on several scales. At the species-level are questions about whether humankind may go extinct. At the social level are threats to the smooth functioning of society and economy. At the individual level are threats to our own mortal bodies.

Major health organizations, including the CDC and the WHO, are already working to chart the health impacts of the Anthropocene. Among the most cited reports in this field is that of the 2015 Rockefeller-Lancet Commission on Planetary Health. As atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gasses increase, so do risks of asthma, allergies, and respiratory infections—including, as a team of Harvard biostatisticians recently showed, COVID-19. Another way to track increasing risk and declining air quality are so-called “Ozone Action” or “Ozone Alert” days, reported via news media and sometimes accompanied by policies including orders to stay indoors or limits on driving cars. The EPA is also working on air quality risks.

Changing water quality also poses health risks. Warmer waters better support waterborne diseases such as cholera, cryptosporidium, dysentery, and other causes of diarrhea. They also support toxic algae blooms and cyanobacteria, visible as the “red tides” haunting beaches from the Gulf of Mexico to Japan. On land, warmer, wetter environments also support the growth of new fungi, some of which threaten people, such as Candida auris, a form of yeast which is increasingly drug resistant and deadly. As Elisabeth Kolbert argues in The Sixth Extinction, it is no accident that many of the pathogens wiping out species today are fungal. In addition to these infectious risks are longer-term chronic risks, such as decreasing access to clean water.

Closely related to water security is food security. As the UN Food and Agriculture Organization, or FAO, stresses, “Climate change will affect all four dimensions of food security: food availability, food accessibility, food utilization and food systems stability.” This begins with problems for farming and food production, including: “increased crop failure, new patterns of pests and diseases, lack of appropriate seeds and planting material, and loss of livestock.” Declining nutrition, like declining air and water quality, weakens human defenses against infections, constituting a slow, chronic health risk.

Health and safety are also threatened in the Anthropocene by extreme weather: heat waves, flooding, and wildfire. Summer heat waves killed 70,000 people across Europe in 2003 and 50,000 in Russia alone in 2010. Last summer was particularly devastating in India and Pakistan, whose record-breaking heat exceeded 120 F or 50 C, and was long-lived, lasting more than a month. The associated drought caused a water crisis that provoked protests and violence. Our warming world also witnesses more devastating wildfires, for example in California and Australia. Last year’s so-called “Black Summer” saw Australia’s worst wildfires in history, killing 34 people, burning 46 million acres and doing more than $4 billion in damages. Smoke traveled across the Pacific to Chile and Argentina.

Rising sea levels are already causing “daylight flooding” or flooding without any rainstorms, in which water rises from below ground level, most often in coastal cities, low-lying areas, and Pacific islands. The 2018 PBS documentary series Sinking Cities examined this problem in New York, Miami, London, and Tokyo. This past summer, Venice saw its worst flooding in 50 years, which the city’s mayor publicly blamed on climate change. The coastal city, famously built on sandbars in a lagoon, was already sinking from land subsidence caused by pumping out groundwater for industry since WWII, and is now threatened by rising sea water. Meanwhile, Indonesia has announced that it will move its capital from Jakarta to Borneo. Like Venice, Jakarta is sinking because of groundwater pumping and land subsidence at the same time that ocean waters rise around it. Due to increased rainfall, inland areas are also at risk, including Paris and the American Midwest, where the swelling Missourri and Mississippi rivers caused over $3 billion in damages in 2019.

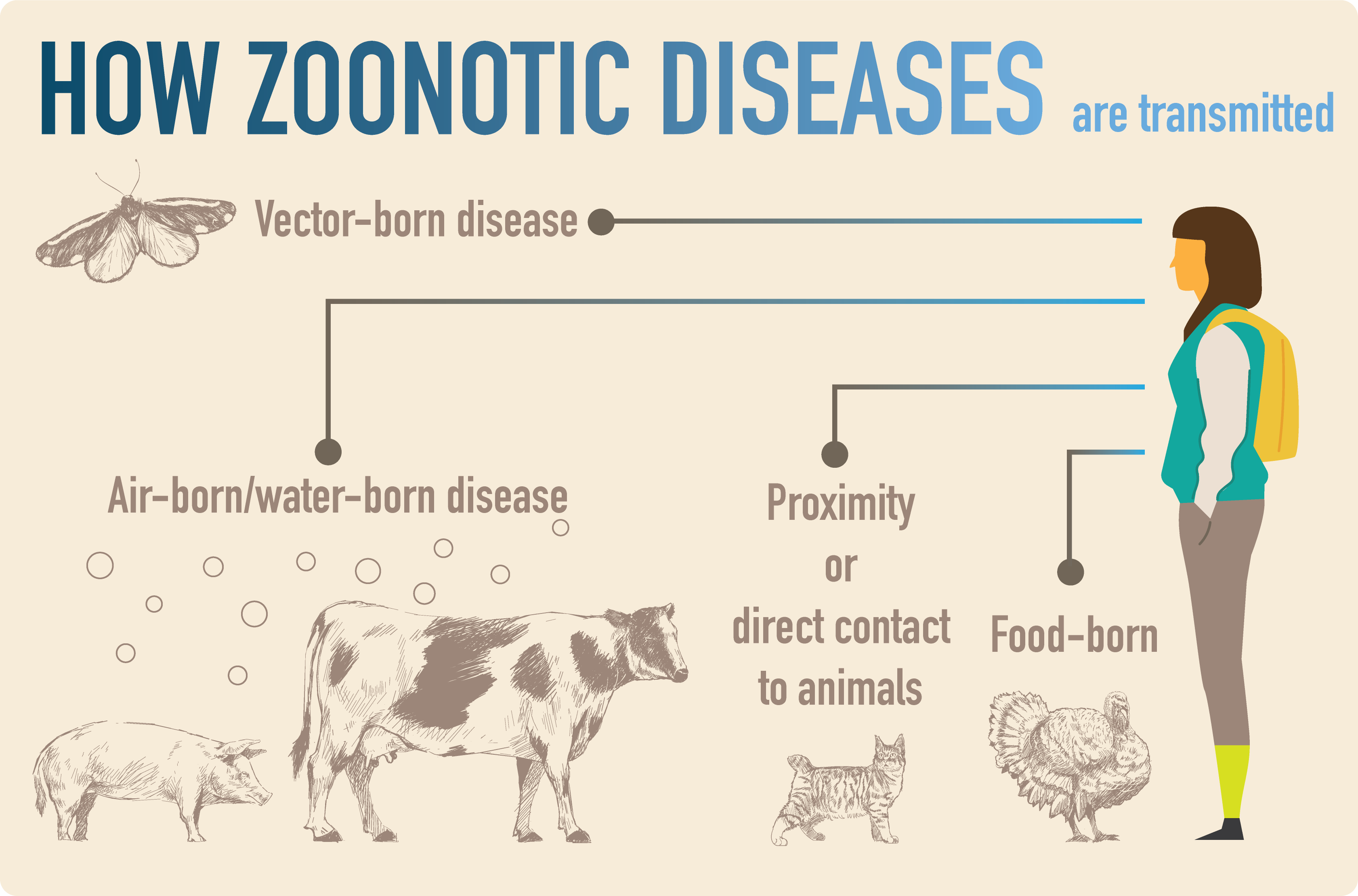

From Ichiko Sugiyama, “Are the risks of zoonotic diseases rising in the Anthropocene due to climate change?“

Disease in the Anthropocene

Pandemics are always human made. We are the only species capable of the high-speed and long-distance travel needed to transport germs around the world while they are still contagious. The way our technology moves goods, people, and vehicles has globalized disease in outflowing ripples of the Columbian Exchange. Air travel and cruise ships have come under growing scrutiny during the COVID-19 pandemic.

But behind these acute risks are chronic issues associated with the Anthropocene. Researchers argue that anthropogenic environmental change transforms infections that we catch from nonhuman species: VBZDs or “vector-borne and zoonotic diseases.” More than two-thirds of all human infections and 60% of emerging infections are zoonoses, infections shared with nonhumans; prominent examples include bubonic plague, malaria, dengue fever, AIDS, Ebola, Zika, swine flu, bird flu, and today’s COVID-19.

Zoonoses become more deadly for humans when we destroy or transform animal habitats, bringing animal populations into closer contact with human society. Back in 2012, the New York Times quoted science writers including David Quammen and Jim Robbins arguing that we are “tearing ecoystems apart” (Quammen’s words), which brings human and animal populations into new, closer relationships, making zoonoses more common and more deadly. Quammen helped popularize the epidemiological term “spillover” for these moments when a disease transfers from one population (the “reservoir”) into another, a novel “host.”

For example, wild animals forage more for food in human settlements when their natural habitats are damaged; similarly, humans lacking steady access to farmed and regulated protein often purchase wild game meat from “wet markets,” where game hunters, vendors, and customers all risk infection. Epidemiologists trace the Wuhan coronavirus outbreak to the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market. Human disasters like warfare or famine create refugees, people who migrate into animal habitats as they struggle with food security. Environmental disasters like flood or drought can also create migrations of animal refugees who wander into human settlements with their pathogens. Human disruptions of natural environments create new pressures to migrate, in which organisms carry their pathogens with them. Brand new studies have implicated bats and pangolins, but also civet cats—though still inconclusively—in the spread of COVID-19. On April 5, news broke that a tiger from the Bronx zoo tested positive for COVID-19 after zookeepers noticed a group of lions and tigers exhibiting symptoms consistent with the disease. This news has troubled the previous consensus among experts that (although the virus can infect cats, chickens, pigs, and ducks), pet and livestock owners should not be concerned about getting the virus from, or giving the virus to, domestic animals. The American Veterinary Medical Association warned people sick with COVID-19 to avoid contact with pets and livestock “out of an abundance of caution.”

In each case, the crucial disruptor allowing nonhuman diseases to flood human society was human activity: the food injustice that causes people to turn to game markets for protein, the rapid transportation networks (cruise ships, airplanes) that move sick people around the globe, and the destruction of animal habitats which drive animals closer to human settlement. Scientific American recently reported that “Destroyed Habitat Creates the Perfect Conditions for Coronavirus to Emerge.” (see also Environmental Health News). For example, humans hunt bats for game meat, but also threaten their habitats with deforestation. Furthermore, like humans, bats live in dense social agglomerations which allow respiratory viruses to spread efficiently. I learned this through conversation with disease historian and OU Provost Kyle Harper, who recently connected the spread of respiratory viruses with human social evolution, particularly urbanization.

Global warming is changing animal migration ranges and reproductive rates in ways that impact disease. As insects and the infections they carry move north into formerly cooler areas, disease ranges shift, too. Changing tick ranges account for the growing Lyme disease problem in the northern and eastern United States. Science writer Mary Beth Pfeiffer calls Lyme disease “the first epidemic of climate change.” Similarly, changing mosquito ranges have brought new threats to us on the southern plains, including the West Nile and Zika viruses.

The preceding shows how zoonotic spillover events, emerging infections, and increasingly widespread and deadly epidemics are important indicators of the Anthropocene.

Beyond the physical, material, and causal connections of the Anthropocene and COVID-19, commentators are increasingly turning to analogies between the pandemic and the Anthropocene (especially climate change) in order to design disaster responses that increase resilience and social justice. University of Rochester physics and astronomy professor Adam Frank calls COVID-19 a “fire drill” for climate change. News sources including The Nation, The Conversation, and The Guardian have called COVID-19 a “dress rehearsal” for climate change—a preview of what will happen if policymakers continue to ignore warnings from scientists. Wired writers called the analogy between COVID-19 and climate change “eerily precise,” while Journalist Shannon Osaka asked “Why don’t we treat climate change like an infectious disease?” BBC environment writer Roger Harrabin argued that any COVID-19 recovery plan “must tackle climate change,” while Greta Thunberg recently called for humanity to “tackle the two crises at once.”

If shutting down flights and cruises is good for combating COVID-19, it is equally good for reducing emissions and removing human stressors from wildlife habitats. But these measures will remain temporary if the global economy returns to business as usual when the pandemic recedes. China and the United States are already rolling back emissions limits in order to jump-start economic recovery. The slower pace and fuel savings of the world under quarantine indicate possible longer-term solutions to a human-made ecological crisis which we have frequently returned to on this blog: a circular economy, zero waste, and degrowth. In short, we will be safer and healthier in the future to the extent that our policies and practices address health issues and ecological issues in an integrated way.

Transmission of zoonotic disease is well represented. Thank you 😊