I actually prefer plastic as a material because it is a material for our times. It represents the now. Ironically it is also ‘archival’, meaning in terms of its longevity it lasts over 100 years. This means that for art, it is a great material.

Claudia Hart (artist/sculptor), “Resolution, Reification,

and Resistance,” 3d Additivist Cookbook.

Not so long ago I had a conversation with a respected curator and gallery director about my research on desktop 3d printing. We discussed the way that process uses plastic filaments in a drawing procedure, one which is ripe with creative exploration and philosophical inquiry regarding the artist’s hand in a mechanized serial process. In response this curator exclaimed, “collectors and institutions will never seriously purchase 3d printed art.”

That seemed odd since contemporary sculptural materials regularly include plastics, fiberglass, epoxy, foam, acrylics, polystyrene, and other seemingly less noble materials than traditional bronze, clay, glass, and steel. Material use of ABS plastic and fiberglass reinforced polyester resin in sculpture began some 50+ years ago. Why would 3d printed objects not be valued with as much artistic potential or economic investment as an art object? Can the 3d printing process be re-contextualized as an artistic endeavor by re-evaluating the aesthetic reality that the layered deposition it makes use of presents?

Naum Gabo “Construction in Space: Two Cones,” 1927. Cellulose nitrate and cellulose acetate. This early plastic lacked the longevity we see with modern plastics and this work cannot be displayed any longer as it has nearly disintegrated. From Architizer. Photo © Nina & Graham Williams/Tate, London 2011 via the Tate Museum |

Donald Judd, Untitled, 1968 (stainless steel and acrylic sheet). At Art Institute of Chicago. |

Plastic is a material devoid of a craft history. Unlike clay, wood, marble, and metals, our creative human history has no artisan or apprenticeship model attached to the building or crafting of plastic. Plastic was subjugated to the specificity of industrial production, and for many of us, how the ubiquitous products of consumerism are spit out is largely a mystery. The form that plastic takes and the absence of any residue of the process that created the object itself serves to inform the way we treat and evaluate the importance of the material on the whole. Somewhere in that curator’s response above, I believe, the idea that plastic is devoid of artistic value is informed by the disconnect of romanticized nostalgia we might apply to materiality. Plastic is a material of convenience and expediency. It evokes sterility over nobility and affection for traditional materials.

But is this changing? And a larger question: what good might come out of a re-evaluation of plastic as an art material through a hand-crafted process?

Adidas running shoe manufactured with 3d printing process by Carbon.

3d printing is not new. The process itself has been around since the early 1980’s. What is new is the explosion of the desktop 3d printing global culture. Now estimated at $7 billion, some nearly one hundred 3d printing manufacturers make cheap and accessible printers for use in homes, elementary schools, maker spaces, universities, and libraries. Combine this with the recent push of accessible 3d printed consumer objects like the Adidas Futurecraft 4d shoe and there is, I contend, a new craft being formulated within our visual culture. We are being attuned to plastic manipulation in a dynamic, informative, and tactile fashion.

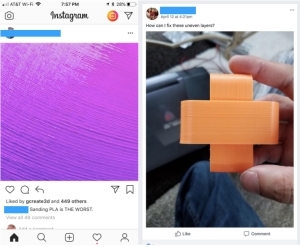

The Fused Filament Fabrication (FFF) process has created a new way to look at the process of making with plastic. No longer are expensive methods for forming plastic necessary to initiate an intimate or personal creative conversation with the material. Instead of using found or discarded plastic refuse from injection molding, vacuum casting, and blow molding for creative re-purposing, individuals are evaluating how they can personally craft plastic. This crafting has led to an explosion of aesthetic considerations and discussions within the myriad of social media posts seeking solutions or tips on how to craft the layered aesthetic of 3d printing better and more precisely.

Individuals who are involved with 3d printing are probably already aware of the Benchy. Touted as a 3d printer “torture test,” this file was designed specifically to evaluate the performance of filament based 3d printers and the associated print settings used in “slicing” software like Cura and Sli3er which generate the g-code to control a 3d printer. The feedback from a Benchy print can inform the operator of the residual aesthetic result of programming code and machine working in tandem. Benchy’s have been printed millions of times across the globe and serve as a primary connective device for troubleshooting and evaluating the 3d printed layered deposition aesthetic.

In her essay “The Honesty of Extrusion” Catherine Scott contends “there is the potential to exploit the extruded aesthetic, largely regarded as a flaw, by exaggerating it and lowering the print resolution to uncover the very essence of the material construction. Laying bare form in this way is not unusual.” I might go a step further by saying that the exploitation of the aesthetic is already leading to a more consciously aware visual acuity regarding plastic manipulation. Plastic is a global vehicle for aesthetic inquiry through the craft of 3d printing. This mini-revolution will have any number of unforeseen consequences and will surely spark any number of debates. However, I see this movement through rose-colored glasses. As an artist and educator, it excites me to see how the materiality of plastic might elevate our sense of responsibility for and the value that we associate with plastic objects. In my mind, I see the relationships among 3d printing’s serial production, plastics, and the overall layered aesthetic as forging a new visual discourse now playing out in architecture, consumer products, and art.

As an artist, for me 3d printing has opened a research interest that associates the act of 3d printing with drawing through programming. In artistic terms, 3d printing is connected to Sol Lewitt’s encoded drawings, which are simple instructions on how to make his drawing through a series of rules to define the task. Similarly, discussions come to mind of Frank Stella’s Black Paintings in Lawrence Alloway’s Systemic Painting, wherein “form becomes meaningful not because of ingenuity or surprise, but because of repetition and extension. The recurrent image is subject to continuous transformation, destruction, and reconstruction; it requires being read in time and space,” and, “The run of the image constitutes a system with limits set up by the artist himself.”

With their serial processes, artists like Lewitt and Stella drew directly from the seriality of manufacturing. 3d printing offers a completely new paradigm for re-investigating those processes by focusing on the machine operator/programmer who can investigate, manipulate, and evaluate a craft in a relationship with machine and material. Whether this new dynamic will lead to a specific change in how we regard plastic is certainly an open question and not one that I’ll make any specific comments about. But, as an artist who thinks about aesthetics in a world where aesthetic concerns are often an afterthought, I am encouraged that 3d printing with plastic is doing something to engage a global community of people who might not have considered their role as a craftspeople before. I am also encouraged that culture might come to value plastic with more sincerity as we see tangible and creative connections to the material, rather than continuing to hold the stereotype of plastic as a cheap commodified by-product that happens to last a long time … even though that is good for artists.